Reimagining Hydropower and Green Hydrogen

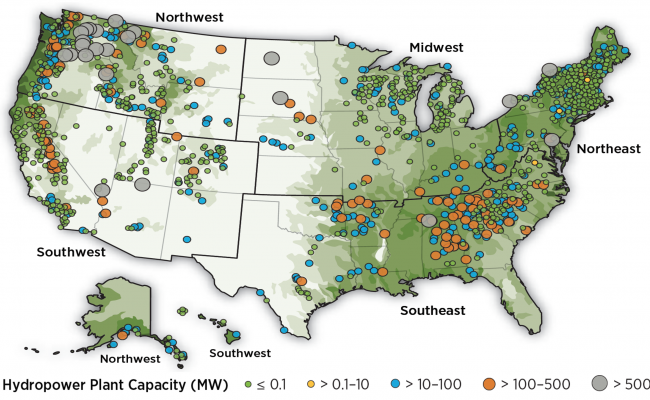

The US, European Union, and other countries that have set net-zero carbon emission targets and participate in the Paris Accord are placing big bets on wind and solar to produce green hydrogen (H2). Here in the US lawmakers and policy makers seem to have overlooked hydropower as a source of renewable energy even though it accounts for 52 percent of the nation’s renewable electricity generation and 7 percent of total electricity generation . For example, indigenous communities and environmental groups are opposed to hydropower because of its impacts on fish, wildlife, and water quality.

Many hydropower owners are taking a hard look at the economic value of their projects in light of climate change, aging infrastructure, increased operating costs due to environmental compliance, and evolving electricity markets. Many small hydropower projects are especially affected by the above factors since they provide only electric energy and not the peaking capacity and ancillary services valued by the electric grid. Nevertheless, these projects have value since a growing number now contain license conditions to reduce environmental impacts when they were initially built. In a previous column, this author also discussed a way for owners of “low impact hydropower” to fully monetize their project’s attributes by seeking renewable energy certificates (RECs).

This author now also suggests that hydropower can play a significant role in jumpstarting the production and distribution of green hydrogen (H2). However, this will require all hydropower owners and developers to reimagine how their projects will operate and diversify their revenue streams over the next 20 years. If hydropower projects can produce sufficient quantities of green H2, they could accelerate efforts to decarbonize natural gas by blending green H2 in the natural gas grid and help states meet their net-zero emissions. On November 23, 2020, Southern California Gas Co. and San Diego Gas and Electric announced the creation of a Hydrogen Blending Demonstration Program . This program is the first in California and the nation.

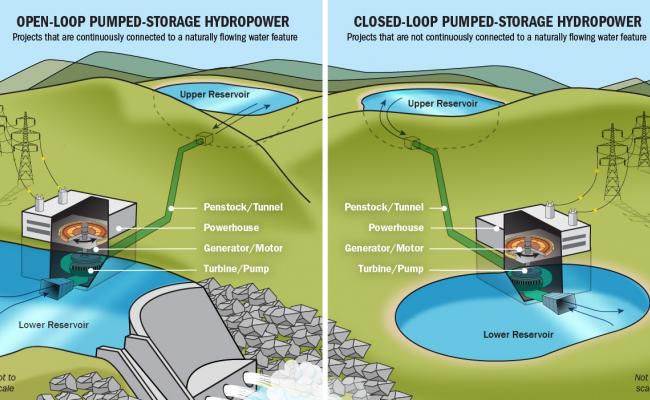

One of the biggest challenges with the hydropower industry has been its laser focus of trying to influence Congress and regulators on streamlining the siting process instead of reimagining a non-traditional role for hydropower outside of the electric grid. The National Hydropower Association (NHA) has influenced both Congress and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to streamline its environmental and regulatory reviews to some degree. The NHA has had some success to date but is still short of what is expected by many hydropower owners and developers . For example, FERC has promulgated an expedited process for issuing original licenses for qualifying facilities at existing nonpower dams and for closed-loop pumped storage projects, pursuant to sections 3003 and 3004 of the America’s Water Infrastructure Act of 2018. NHA has also seen progress in extending the time to construct new hydropower projects and set a minimum FERC license term of 40 to 50 years instead of 30 to 50 years.

Despite the above progress, FERC’s regulatory reviews remain some of the most comprehensive and take years for staff to complete, despite the size of the hydropower project. Both small and large hydropower projects that were licensed or constructed prior to passage of the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) are especially challenged by new environmental conditions included in new licenses and operating conditions.

NEPA REVIEW, POWER PURCHASE AGREEMENTS, AND FINANCING CHALLENGES

Comprehensive NEPA reviews and compliance with environmental laws during the life of a hydropower project are here to stay and are not likely to change. Despite being a form of renewable energy, many hydropower projects are lightning rods for public controversy and duplicative regulation by other federal and state agencies other than FERC. The controversy centers on competing use of rivers. Many indigenous communities and environmental groups and environmental agencies want to use water to restore anadromous fish runs and protect fish, wildlife, water quality, and recreation. In contrast, hydropower owners and other communities want to use the project for power generation, water supply, and flood control and other developmental uses, including the prevention of salt-water intrusion on ground water in coastal areas. Download the complete article in the Climate & Energy Journal. [node:read-more:link]